William Faulkner's The Sound and The Fury

Share

William Faulkner stands among the most towering literary figures of the twentieth century, a Nobel laureate whose novels, stories, and plays forever transformed the contours of American literature. With a voice deeply rooted in his native Mississippi, Faulkner crafted a fictional universe that probes the tumultuous history, psychology, and culture of the American South. His innovative narrative techniques—marked by stream of consciousness, shifting perspectives, and intricate chronologies—continue to challenge and inspire readers worldwide.

Faulkner’s Literary Life

Born in New Albany, Mississippi, in 1897, William Cuthbert Faulkner spent much of his life steeped in the history and folklore of his homeland. Though he was never a prolific traveler, the landscapes and lives of the South became inexhaustible sources of inspiration. Faulkner’s literary career began in the early 1920s, initially with poetry and a few lesser-known novels, but it was his transition to prose fiction that revealed the depths of his genius.

Faulkner’s upbringing and the socio-political context of early twentieth-century Mississippi permeated his worldview and works. His early attempts at poetry, such as "The Marble Faun" (1924), show a young writer searching for voice and subject. It wasn’t until Soldiers’ Pay (1926) and Mosquitoes (1927) that Faulkner began to experiment with prose fiction—though success was still elusive.

Faulkner persisted, and in 1929 published The Sound and the Fury, a novel that would inaugurate his signature style and set him on the path to literary immortality. Over the next three decades, Faulkner produced a staggering array of novels, stories, and screenplays, earning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1949 "for his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel."

Literary Style and Innovations

Faulkner is perhaps best known for his radical experimentation with narrative form. His works often employ:

· Stream of Consciousness: Most famously in "The Sound and the Fury," Faulkner plunges readers into the unfiltered inner worlds of his characters.

· Non-linear Chronology: The events of his novels rarely unfold in straightforward fashion; instead, Faulkner fragments time, creating a kaleidoscopic effect. Narratives such as "Absalom, Absalom!" leap across decades, retelling events from multiple perspectives.

· Multiple Narrators: Faulkner's novels frequently feature several narrators, each with a distinct voice and viewpoint, adding layers of ambiguity and depth.

· Invented Geography: Faulkner’s mythical Yoknapatawpha County, modeled on Lafayette County, Mississippi, serves as the setting for most of his fiction—a place as real and detailed as any in literature.

· Dense, Lyrical Prose: Faulkner’s sentences can be sprawling and complex, weaving together history, memory, and emotion with poetic resonance.

Faulkner’s style is often challenging—at times elliptical, at other times richly descriptive—but always in service of probing the psychological and moral undercurrents of his characters and their world. His writing addresses themes of decay and renewal, race, class, family, and the weight of the past upon the present.

Major Works of Fiction

Faulkner’s body of work is immense, but several novels stand out as his most influential and celebrated:

The Sound and the Fury (1929)

Perhaps Faulkner’s most famous novel, The Sound and the Fury tells the story of the Compson family’s decline through four distinct sections, each narrated by a different character. The first section, delivered in the stream-of-consciousness style of Benjy, a cognitively disabled man, is a masterpiece of literary innovation. Subsequent sections reveal the perspectives of Quentin, whose torment leads to suicide; Jason, whose bitterness is palpable; and a final, omniscient narrative that attempts to piece the family’s tragedy together.

Central to the novel is Faulkner’s motif of time—its passage, its permutations in memory, and its iron grip upon the lives of the Compsons. The fractured narrative, shifting tenses, and disjointed chronology evoke the chaos and sorrow at the heart of the family.

As I Lay Dying (1930)

Written in just six weeks, As I Lay Dying chronicles the arduous journey of the Bundren family as they transport the body of their matriarch, Addie, to her hometown for burial. The novel features fifteen narrators, each offering a unique vantage point on the events at hand. Through interior monologue and shifting perspectives, Faulkner explores themes of death, grief, and familial obligation with dark humor and existential depth.

The novel is celebrated for its technical daring and its unvarnished depiction of rural Southern life. The famous line—“My mother is a fish”—epitomizes Faulkner’s ability to render the inner workings of the human mind with startling clarity.

Sanctuary (1931)

In Sanctuary, Faulkner turns toward the gothic and the grotesque, weaving a tale of violence, corruption, and sexual abuse in the fictional town of Jefferson. The novel’s protagonist, Temple Drake, is drawn into a nightmarish world of criminality and moral breakdown. Sanctuary shocked contemporary readers and remains a disturbing portrait of a society on the edge.

Light in August (1932)

Light in August is often viewed as one of Faulkner’s finest works, a sprawling tale that interweaves the lives of Lena Grove, searching for the father of her unborn child; Joe Christmas, a man of ambiguous racial identity haunted by violence; and the reclusive minister Gail Hightower. The novel addresses issues of race, identity, and community, set against the backdrop of Yoknapatawpha County.

Faulkner’s depiction of Joe Christmas is particularly notable—the character’s struggle with his sense of belonging and the ambiguity of his heritage mirrors enduring American anxieties about race and difference.

Absalom, Absalom! (1936)

Considered by many to be Faulkner’s masterpiece, Absalom, Absalom! recounts the rise and fall of Thomas Sutpen, a self-made plantation owner intent on establishing a dynasty. Told through a series of nested narrations, the novel meditates on history, memory, and the legacies of slavery and ambition in the South.

Absalom, Absalom! is as much about the act of storytelling as it is about its subject—each retelling of Sutpen’s life reveals more about the narrator than about Sutpen himself, resulting in a dizzying palimpsest of truth and myth.

Other Significant Works

· The Unvanquished (1938): A series of linked stories tracing a family’s experiences during and after the Civil War.

· The Hamlet (1940): The first volume in the "Snopes Trilogy," chronicling the rise of the cunning and unscrupulous Snopes family.

· Go Down, Moses (1942): A novel-in-stories exploring the intricate relationships among generations of a Southern family, including descendants of both enslavers and enslaved people.

· Intruder in the Dust (1948): A meditation on race and justice, centering on the wrongful accusation of a Black man in Mississippi.

Legacy and Influence

William Faulkner’s literary life was marked by an unceasing drive to innovate and confront the deepest questions of human existence. His style, at once ambitious and uncompromising, continues to influence writers and scholars across the world. Faulkner’s works probe the intricacies of language, memory, and identity, offering a vision of the South—and of America—at once particular and universal.

As a chronicler of history, Faulkner insisted that “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” His fiction compels readers to grapple with the burdens of ancestry and the possibility of redemption. Today, Faulkner remains a touchstone for explorations of narrative form, psychological depth, and the inexhaustible complexity of human life.

The Plot of The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929) is a masterwork of modernist literature, celebrated for its radical experimentation with narrative structure, stream-of-consciousness technique, and the unflinching portrait it paints of a Southern family in decline. The novel unfolds the unraveling of the Compsons, a once-aristocratic Mississippi family, as they confront the encroachment of modernity, the erosion of tradition, and their own irreparable wounds.

Structure and Narrative Approach

Faulkner divides the novel into four distinct sections, each narrated by a different voice and offering a unique lens through which to witness the Compson family’s fate. By weaving together the internal monologues of his characters—often fragmented, nonlinear, and emotionally raw—Faulkner immerses the reader in the labyrinth of memory, grief, and longing that defines the Compson experience. Each narrative voice is shaped by its own limitations, obsessions, and distortions, yielding a multifaceted, almost cubist vision of a family haunted by loss.

April 7, 1928: Benjy’s Section

The novel opens with the voice of Benjamin “Benjy” Compson, the intellectually disabled youngest son, whose perception of time is non-linear and whose thoughts intertwine memories from the past and present. Benjy’s world is a swirl of sensations, colors, and sounds; events from his childhood merge with those of his adult life with little distinction. Through Benjy’s section, the reader experiences the dissolution of the Compson family not as a sequence of events but as an unrelenting emotional undertow.

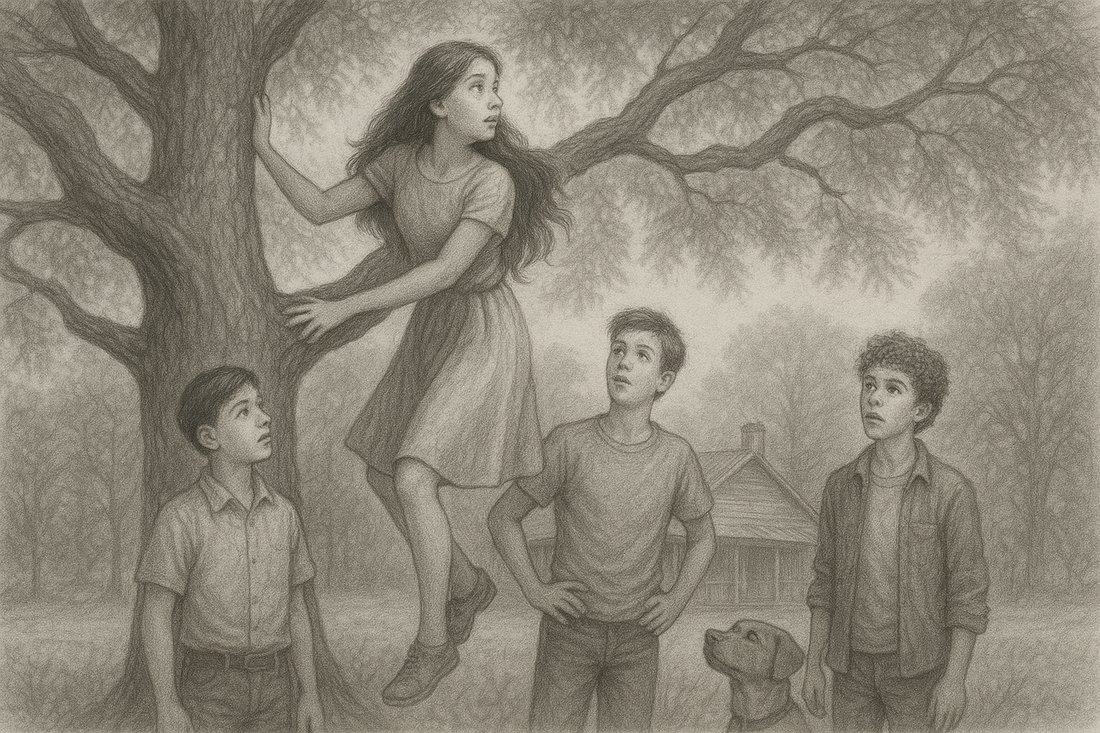

Benjy’s mind moves fluidly between his early years, when his beloved sister Caddy was the axis of his universe, and the present, where loss and silence prevail. The reader pieces together that Caddy was a nurturing figure in Benjy’s life, and her absence signals a profound rupture. Benjy’s memories return obsessively to moments in the family’s past: Caddy climbing a tree and muddying her drawers, her comforting presence, and the trauma of her eventual exile. He also recalls traumatic events, such as the death of his grandmother, Damuddy, and the sale of the family’s pasture—signifying both emotional and economic decline. Benjy’s narrative, while at times bewildering, offers a deeply intimate sense of the Compsons’ suffering and isolation. He is, in many ways, the living embodiment of the family’s brokenness.

June 2, 1910: Quentin’s Section

The second section transports the reader to Harvard University in 1910 and is narrated by Quentin Compson, the sensitive and introspective eldest son. Quentin’s section is perhaps the most stylistically daring, as his thoughts spiral through time, memory, and obsession, often collapsing conventional syntax and punctuation under the weight of his anguish.

Quentin’s consciousness is dominated by his relationship with Caddy, whose sexual independence and subsequent disgrace (she becomes pregnant out of wedlock) serve as both the source of his despair and the emblem of the Compson family’s fall from grace. Unable—or unwilling—to negotiate the changing values of the modern world, Quentin becomes fixated on notions of honor, purity, and the preservation of the Old South’s ideals. His efforts to defend Caddy’s reputation and the family’s name are ultimately futile; he is powerless to halt the march of time or to rewrite the past.

Over the course of a single day, Quentin wanders the streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts, wrestling with guilt, confusion, and a sense of impending doom. He recalls the conversations with his father, Mr. Jason Compson III, whose philosophical skepticism and detachment undermine Quentin’s efforts to find meaning or solace. Quentin’s narrative culminates in his suicide, a desperate attempt to escape a world in which he can find no redemption.

April 6, 1928: Jason’s Section

The third section shifts to the point of view of Jason Compson IV, the caustic, embittered third son. Jason’s narrative is the most straightforward and linear, reflecting his own narrow and self-serving outlook. By the time of his section, the Compson family is in shambles: their financial resources depleted, their social position eroded, and their familial bonds almost entirely severed.

Jason is obsessed with money, control, and resentment—particularly toward his niece, Miss Quentin (Caddy’s daughter, who now lives with the Compsons), and toward the memory of Caddy herself. He has become the primary provider for the family, though he does so grudgingly and with a deeply cruel edge. He routinely embezzles the money Caddy sends for Miss Quentin’s support and vents his frustrations on his hypochondriac mother, Caroline, and on Benjy, whom he views as a burden and a source of shame.

Jason’s narrative is punctuated by scenes of confrontation, bitterness, and mounting chaos. The family’s isolation is complete, and Jason’s attempts to maintain order are increasingly desperate. His antagonism toward Miss Quentin reaches a climax when she runs away, stealing the money he has hoarded, which further destabilizes the already precarious family structure.

April 8, 1928: The Appendix (Dilsey’s Section)

The novel’s final section shifts to a third-person perspective, centering on the Compsons’ Black servant, Dilsey Gibson, who has served the family for generations. Dilsey’s presence offers a sense of continuity, compassion, and resilience that stands in marked contrast to the Compsons’ fragmentation. Through her eyes, Faulkner reveals the full extent of the family’s decline but also gestures toward the possibility of endurance and faith.

On Easter Sunday, Dilsey brings Benjy and the rest of the family to church, seeking solace and meaning amid loss. Her quiet dignity and determination provide a form of hope that the Compsons themselves are unable to grasp. In the novel’s closing scenes, Benjy is returned to his routine—a drive through the town that is thrown into chaos when Jason, in a fit of rage, upends the carriage’s order. For an instant, Benjy’s world is rendered unbearable; when the order is restored, he falls silent, staring “through the curling flower spaces.” The ending is ambiguous, at once tragic and oddly peaceful.

Major Themes and Motifs

The Collapse of the Southern Aristocracy: Throughout the novel, the Compsons’ fall from grace serves as a microcosm for the decline of the Old South. Their inability to adapt to changing social and economic realities is mirrored in their psychological disintegration.

Time and Memory: Faulkner’s narrative intricacies reflect his preoccupation with the ways time wounds and shapes identity. The characters are unable to escape the past, which intrudes upon the present in unpredictable ways.

Innocence and Loss: The loss of Caddy’s innocence—and the family’s obsession with it—serves as the emotional core of the novel. Each brother’s response to this loss highlights their own fatal flaws.

Fragmentation of Perspective: Faulkner’s use of multiple perspectives—each unreliable in its own way—underscores the subjectivity of memory and the impossibility of a single, authoritative truth.

The Significance of Characters in Advancing The Sound and the Fury

William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury is a novel renowned for its complex structure, shifting perspectives, and linguistic innovation. At its heart, the novel’s power and lasting legacy stem from its vivid, flawed, and deeply human characters, each of whom not only advances the plot but also embodies the novel’s central themes—time, memory, loss, and the collapse of Southern aristocracy. Through the unique renderings of Benjy, Quentin, Jason, and Dilsey, Faulkner crafts a narrative that explores the fragmentation of perspective and the unrelenting passage of time, while probing the psychological torment and resilience that define the Compson family.

Benjy Compson: Innocence, Loss, and the Tragedy of Perception

Benjy, the youngest Compson sibling, is mentally disabled and nonverbal, yet his section opens the novel with a profound, stream-of-consciousness account that is both chaotic and deeply poetic. Benjy’s perception of time is nonlinear—past and present intermingle—reflecting Faulkner’s preoccupation with memory and the impossibility of escaping trauma. Benjy’s narrative is one of pure sensation; he experiences the world through sound, smell, and tactile cues, which imbue his section with a childlike innocence yet also a pervasive sense of sorrow.

The significance of Benjy’s character lies in his role as a living embodiment of loss. His obsessive attachment to his sister Caddy, whose fall from innocence marks the family’s decline, is the emotional core of his section and arguably, the novel itself. Benjy’s inability to understand the world rationally amplifies the tragedy of the Compsons: their pain is not just a product of circumstance but a feature of their very existence, felt most acutely by the one least able to articulate it. Faulkner uses Benjy’s innocence and sensory experience to highlight the impact of time and memory. Benjy’s world is ordered by routine and disrupted by change, making him a figure through which the reader feels the emotional fragmentation and instability of the family.

Quentin Compson: The Burden of Time and the Obsession with Honor

Quentin, the eldest son, is a Harvard student who represents the tortured intellectual—consumed by guilt, honor, and the impossibility of reconciling the past with the present. His section, rendered in a highly introspective, fractured style, is a descent into psychological turmoil, culminating in his suicide. Quentin’s obsession with Caddy’s lost innocence and his rigid adherence to Southern codes of honor propel his narrative, highlighting the impossibility of upholding outdated values in a changing world.

Quentin’s significance is multi-faceted. First, his character embodies the central motif of time’s inexorable passage. His struggle with clocks, memories, and timepieces reflects a futile desire to halt the decay of the Compson family and, by extension, the Old South. Second, Quentin’s internal monologue and shifting sense of reality advance Faulkner’s narrative technique: the stream-of-consciousness style serves not just as a window into Quentin’s mind but as a literary device for articulating the fragmentation of truth and the unreliability of memory. Quentin’s suicide is the culmination of the family’s inability to adapt—a literal and figurative surrender to the forces of time, loss, and psychological destruction.

Jason Compson IV: Control, Resentment, and the Collapse of Order

Jason, the third Compson sibling, emerges as the family’s reluctant, bitter provider following the death of his father. His narrative is marked by cruelty, resentment, and a desperate need to maintain order in a chaotic household. Unlike Benjy and Quentin, Jason’s voice is direct, sardonic, and often caustic; he is obsessed with material wealth, power, and control, venting his frustrations on his family members and embezzling the funds intended for Caddy’s daughter, Miss Quentin.

Jason’s significance in advancing the novel is twofold. On the surface, he represents the materialistic, pragmatic response to crisis, contrasting with Benjy’s innocence and Quentin’s idealism. Yet his attempts at control are ultimately futile, as the family splinters and Miss Quentin escapes with the money he has hoarded. Jason’s narrative advances the plot toward its climax—the literal and symbolic loss of the family’s last vestiges of security—and mirrors the theme of the Southern aristocracy’s collapse. His inability to maintain order, coupled with his antagonism toward Miss Quentin and his bitterness over the past, underscores the novel’s exploration of psychological disintegration and the impossibility of restoring the lost grandeur of the Compsons.

Dilsey Gibson: Resilience and the Possibility of Endurance

The novel’s final section shifts to Dilsey, the Compsons’ Black servant, whose perspective is rendered in the third person. Dilsey stands in sharp relief to the family’s fragmentation; she embodies compassion, faith, and endurance. While the Compsons unravel, Dilsey provides continuity, caring for Benjy and the others with quiet dignity. Her attendance at the Easter Sunday church service, seeking solace and meaning amid loss, elevates the narrative and gestures toward the possibility of transcendence.

Dilsey’s character is significant for several reasons. She is the only figure in the novel capable of providing genuine hope and stability. Whereas the Compsons are imprisoned by their memories and obsessions, Dilsey’s faith offers a counterpoint—a means of enduring suffering and finding meaning despite adversity. Her presence marks a subtle critique of the social hierarchy and racial divisions of the South, suggesting that the capacity for compassion lies beyond the boundaries of class, race, or family. Through Dilsey, Faulkner introduces the possibility that endurance, rather than aristocratic pride or futile nostalgia, is the true measure of greatness.

Caddy Compson and Miss Quentin: The Absent Center and Generational Tension

Although Caddy Compson—the sister whose loss of innocence precipitates the family's downfall—never narrates her own section, her significance is omnipresent. Caddy is the absent center of the novel; each brother’s narrative is shaped by their relationship to her and their reaction to her transgressions. Benjy mourns her absence, Quentin is consumed by his inability to protect her, and Jason is embittered by the financial and social consequences of her actions.

Miss Quentin, Caddy’s daughter, becomes the focal point of Jason’s resentment and the embodiment of generational tension. Her eventual escape with Jason's stolen money marks the final rupture within the family, signifying the complete collapse of the Compson household. Both Caddy and Miss Quentin highlight the novel’s concern with innocence, loss, and the inability to recover what is gone. Their significance lies in their roles as catalysts for change—Caddy’s absence and Miss Quentin’s rebellion destabilize the family and propel the narrative toward its tragic conclusion.

Advancing Themes Through Character

Faulkner’s use of multiple perspectives—each unreliable, fragmented, and subjective—serves not only to advance the plot but also to deepen the novel’s exploration of truth, memory, and the limits of understanding. The characters’ psychological complexities and their interactions with time reflect the collapse of the Southern aristocracy, the impossibility of recapturing innocence, and the inevitability of loss. Through Benjy, Quentin, Jason, Dilsey, Caddy, and Miss Quentin, Faulkner constructs a tapestry of voices that, in their dissonance, reveal the profound tragedy and enduring humanity at the heart of "The Sound and the Fury."

Setting as Symbol and Catalyst

The setting of The Sound and the Fury—Yoknapatawpha County, and more specifically the decaying Compson estate in Jefferson, Mississippi—is not merely a backdrop but a vital force that shapes the narrative and the fates of its characters. The Compson home, once emblematic of Southern gentility and aristocratic pride, stands in gradual decline, its physical deterioration mirroring the dissolution of the family itself. The crumbling house, overgrown grounds, and oppressive Southern climate evoke a sense of stagnation and suffocation, underscoring the persistent weight of the past that the Compsons cannot escape.

This setting amplifies the novel's themes of loss and disintegration. The social and historical context of the postbellum South—marked by shifting racial hierarchies, economic upheaval, and the fading legacy of the old order—permeates every interaction and internal struggle. The Compsons’ inability to adapt to these changes isolates them; their home becomes a mausoleum of memory and regret, with each member haunted by ghosts of former grandeur and irreparable mistakes.

Moreover, the broader landscape of Jefferson sharpens the contrasts between the insular world of the Compsons and the evolving realities beyond their gates. The town itself, with its church bells, train whistles, and bustling streets, offers a counterpoint to the family’s claustrophobic decline, yet remains ever-present—reminding the Compsons of their diminished place in a world that moves relentlessly forward. Faulkner uses the setting to ground the reader in the specificity of the Southern experience while simultaneously opening the narrative to questions of universality: the inevitability of change, the passage of time, and the human yearning for meaning in the face of loss.

In this way, the setting is both a symbol and a catalyst, advancing the novel by reinforcing its themes, shaping its characters, and situating the Compson tragedy within the broader tapestry of Southern and American history.

Modernist Features and Concepts in The Sound and the Fury

William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury is widely regarded as a cornerstone of American modernist fiction—a work that not only exemplifies the movement’s characteristics but also pushes its boundaries through radical experimentation in style, structure, and theme. Written in 1929, the novel explores the decline of the Compson family in Mississippi, unraveling its story through fractured perspectives and linguistic innovation. In its relentless probing of consciousness, time, and truth, "The Sound and the Fury" stands as a testament to the anxieties and ambitions that shaped modernist literature in the first half of the twentieth century.

Fragmented Structure and Multiplicity of Perspectives

A defining feature of modernist fiction is its break with linear, omniscient narration. Faulkner’s deployment of four distinct narrative sections—each with its own voice and temporal logic—places The Sound and the Fury squarely within this tradition. The first section is narrated by Benjy, whose intellectual disability renders his perception of time and causality profoundly nonlinear. Quentin’s section, a feverish stream of consciousness set on the day of his suicide, plunges the reader into the chaos of memory, guilt, and existential despair. Jason’s narrative, though more conventionally realistic, is saturated with bitterness and self-justification, while the final section, centered on Dilsey, approaches a form of limited omniscience and offers a rare glimpse of moral steadiness.

This multiplicity of perspectives, none of which can claim objective truth, is deeply modernist. Rejecting the Victorian impulse toward coherence and closure, Faulkner’s structure offers instead a collage of conflicting subjectivities. The reader must actively engage in the construction of meaning, piecing together the family’s history from unreliable narrators and ambiguous events. In this way, the novel enacts the modernist conviction that reality is inherently fragmented and elusive, accessible only through partial, contingent glimpses.

Stream of Consciousness and the Exploration of Inner Life

Faulkner’s narrative technique owes much to the innovations of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, whose stream-of-consciousness methods sought to capture the flux of thought and sensation. Benjy’s section, in particular, immerses the reader in a world devoid of temporal boundaries—past and present intermingle in his mind, producing a narrative that mimics the workings of memory itself. Quentin’s section intensifies this approach, with its densely associative passages and disjointed syntax reflecting a mind in turmoil.

Such experimentation with narrative form is a hallmark of modernist literature. By foregrounding consciousness over external events, Faulkner draws the reader into the psychological landscapes of his characters, illuminating their obsessions, anxieties, and desires. The language bends and fractures under the weight of experience, yielding new rhythms and meanings. This emphasis on the subjective experience—particularly as it resists rational organization—places The Sound and the Fury firmly within the modernist tradition.

The Collapse of Traditional Values and the Search for Meaning

Modernism is often characterized by its sense of dislocation—its portrayal of a world in which inherited systems of meaning have broken down. The Compson family, once pillars of Southern gentility, embody this collapse: their estate decays, their values erode, and their relationships unravel. The absent center of Caddy, whose innocence and transgression haunt every narrative, becomes a symbol of irrecoverable loss. Benjy’s mourning, Quentin’s obsession with purity and honor, and Jason’s fixation on money and control all reveal the inability to adapt to the changing realities of the postbellum South.

Yet this dissolution is not merely regional or historical; it is existential. Faulkner’s characters struggle to locate meaning in a world that has ceased to offer it. Quentin’s suicide marks the ultimate renunciation of hope, while Jason’s cynicism is its bitter counterpart. Miss Quentin’s rebellion and Dilsey’s endurance gesture toward new possibilities, yet the novel remains suffused with the sense that redemption is elusive, that the past cannot be recovered.

This preoccupation with alienation, loss, and the search for significance is a central concern of modernist fiction. Faulkner’s treatment of these themes is both specific—rooted in the peculiarities of Southern history—and universal, speaking to the condition of modern humanity adrift in a world of shattered certainties.

Temporal Dislocation and the Problem of Memory

The modernist fascination with time is nowhere more evident than in The Sound and the Fury. Faulkner’s narrative does not proceed chronologically; instead, it circles back upon itself, revisiting key moments from different angles and at different points in the characters’ lives. Benjy’s section dissolves the distinctions between past and present, while Quentin’s narrative is consumed by the impossibility of escaping memory. Jason’s relentless forward motion is itself a reaction against the weight of history, and Dilsey, the only character to span the entirety of the Compson experience, endures time’s ravages with stoic resilience.

This manipulation of time serves multiple purposes. It reflects the subjective nature of experience—the way in which the past continually intrudes upon the present, shaping identity and perception. It also enacts the modernist suspicion that time itself is unstable, that the comforting narratives of progress and continuity are illusions. In Faulkner’s hands, memory is both a source of anguish and a means of survival; it is the mechanism by which characters understand themselves, yet also the trap from which they cannot escape.

Language, Ambiguity, and Innovation

One of modernism’s most radical gestures is its experimentation with language. Faulkner pushes this experimentation to its limits, especially in the first two sections of the novel. Benjy’s narrative, stripped of conventional logic, challenges the reader to decode his sensations and associations. Quentin’s section fractures syntax and meaning, offering fragments of thought, dialogue, and memory that resist easy interpretation.

The result is a text marked by ambiguity and indeterminacy. The reader is never given stable ground; meanings shift and dissolve, demanding active engagement and interpretation. This distrust of linguistic transparency is a defining trait of modernist writing, which seeks to capture the complexity and instability of thought and experience.

Setting and Historical Context as Modernist Catalyst

Faulkner’s use of setting—Yoknapatawpha County and the decaying Compson estate—serves not just as a backdrop but as a catalyst for the novel’s modernist concerns. The estate’s decline mirrors the collapse of the old social order, and the oppressive climate evokes the suffocation of memory and tradition. The juxtaposition between the insular world of the Compsons and the bustling town of Jefferson underscores the tension between stasis and change, isolation and engagement.

The novel’s Southern setting grounds it in particular historical realities: the legacy of slavery, the shifting racial and economic hierarchies, the fading grandeur of the aristocracy. Yet Faulkner uses these particulars to probe questions of universality—the inevitability of loss, the passage of time, the search for meaning in a world transformed by modernity.

Bibliography

Faulkner, William. The Sound and the Fury. Vintage International, 1990.

· Faulkner, William. As I Lay Dying. Vintage International, 1990.

· Faulkner, William. Light in August. Vintage International, 1990.

· Faulkner, William. Absalom, Absalom! Vintage International, 1990.

· Faulkner, William. Sanctuary. Vintage International, 1993.

· Bleikasten, André. Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury: The Decline of the Compsons. Indiana University Press, 1976.

· Matthews, John T. The Play of Faulkner's Language. Cornell University Press, 1982.

· Millgate, Michael. The Achievement of William Faulkner. University of Georgia Press, 1986.

· Polk, Noel and Stephen M. Ross, editors. “Reading Faulkner: The Sound and the Fury.” University Press of Mississippi, 1996.

· Sundquist, Eric J. Faulkner: The House Divided. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.